There are places that exist only in darkness. Narrow strips of highway bisecting the occasional conglomeration of synthetic light. Neon beer signs, glowing gas prices and glimmers of moonlight on a cloudless night provide the only proof of their existence. Theses places exist somewhere between A and B, between sleep and dreams, between

last year and

this year. If you're lucky enough to hit a REM cycle while belted into the passenger seat, they cease to exist at all. They are the cities and towns and truck stops and trailers that dot the map en route to a destination waterway. With sleep nagging at your consciousness, there is an urgency to put these places behind you. With a hurricane on your heels, you can't put them behind you fast enough.

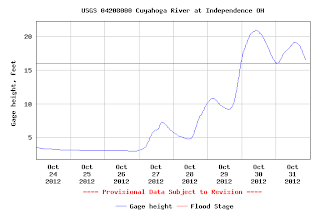

We came with a stated goal of finding steelhead, solitude, and a change of scenery. Perhaps more than anything though, we came because our home rivers were about to overtake their banks. As it turns out one of the best places to ride out a hurricane is on a steelhead stream hundreds of miles away. Whether it has steelhead in it or not is a matter of semantics.

The trip served as a dichotomous snapshot of Mother Nature's mood swings; On one side displaying her most benevolent gifts to the angler in the form of wild trout and steelhead at the peak of their colors...

On the other, days and days of rain with no end in sight. Rivers swelling to historical levels, cities and towns and lives being washed away.

Meanwhile we're reminded to count our blessings as we seek solace somewhere between feast and famine, hoping that when the rivers come down the most we have to worry about is whether there are steelhead in them or not.